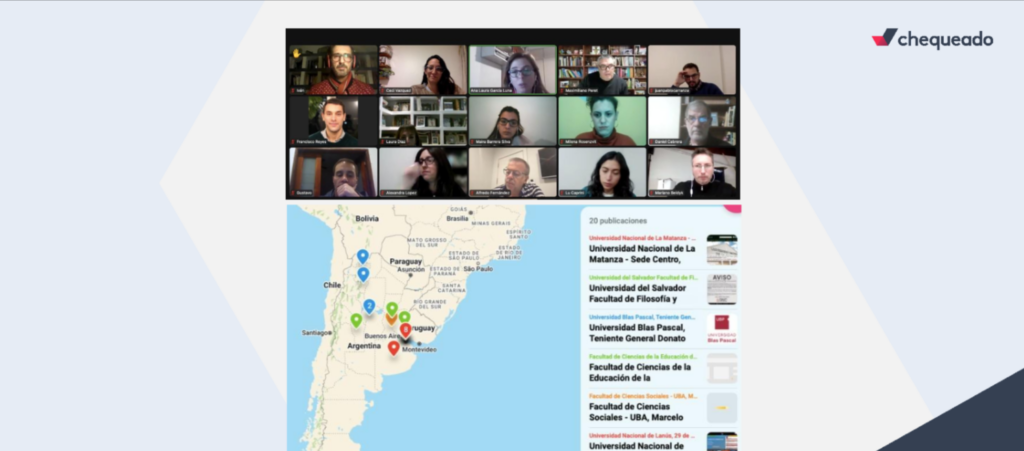

Chequeado expects to expand this network to other countries in the region next year. (Photo: Courtesy)

It is increasingly common to talk about fake news and fact-checking in journalism. Even so, university curricula in journalism in Latin America often do not include courses aimed at teaching fact-checking methodology, nor are there any master's or postgraduate journalism degrees specializing in fact-checking.

In this effort to bring fact-checking techniques to universities, the Argentine organization Chequeado, with the support of Google News Initiative, invited news organizations Verificado (from Mexico), Colombia Check (from Colombia), Convoca and Ojo Público (both from Peru) to form a 'Latin American network of fact-checking trainers,' which will allow journalists and university professors from these countries to act as multipliers.

"We created a course for teachers in these four countries. The idea is that each teacher will then take this information to the classroom. The minimum goal we set ourselves is to reach 500 students," Milena Rosenzvit, coordinator of Chequeado's education program, told Latam Journalism Review (LJR). "We don't want it to be just theory. Rather, we want them to really learn to write a story following the methodology. We hope to create a project that can scale, so journalism degrees in the region can increasingly begin to incorporate this content.”

LJR spoke with the leaders of this network to learn about the activities to be carried out in each country. Also, to understand the situation of fact-checking education at the university level in the region.

Since 2014, the Argentine website Chequeado has already created training projects for journalists and students in Latin America and the Caribbean. Chequeado is the leader of the 'Latin American network of fact-checking trainers.' According to the data published on their website, Chequeado has trained more than 7,000 journalists around the world.

"There are few fact-checking organizations like ours that have a strong education or training focus. It is true that we have done many courses for journalists or journalism students, and other organizations in Latin America have also done so, but the demand is so high that sometimes we can't keep up with it," Rosenzvit said.

A course of only a few hours is sometimes not enough to fully learn the fact-checking methodology. That is why, in this case, there will be a series of online workshops with hands-on projects and live feedback. "The course will last about five weeks with weekly sessions. In addition, there is additional work where verification notes must be written," she said.

Chequeado hopes next year to expand this network to other countries in the region. They have received a lot of interest from organizations and professors in Central America who want training in this field. "Our vision is not to just offer the course and have teachers try it in their classrooms and that’s it. We want to create a community of trainers who can keep in touch through different channels and share resources, strategies and experiences," Rosenzvit said.

Ojo Público was the first news outlet to add a verification team in Peru. It started in the same year the news outlet was founded, in 2015. Since then, they have promoted fact-checking, held workshops and have been involved in training new fact-checkers.

"This initiative goes a step further and aims to introduce this practice at the level of journalism professors, to bring it closer and for it to be more common in academia," David Hidalgo, journalism director of Ojo Público, said. (Photo: Courtesy)

David Hidalgo, news director of Ojo Público, told LJR that for a while it was difficult to promote fact-checking even among aspiring journalists. "It was difficult for them to grasp the true sense and rigor that are necessary to apply this methodology to create content. However, over time we showed that this type of content not only raised the quality of journalism but also had a significant potential to go viral, at a time when many news outlets began to develop digital strategies to grow their audience," Hidalgo said.

Likewise, the COVID-19 pandemic that had a considerable effect on Peru made clear the need for journalism to confront the phenomenon of disinformation through fact-checking tools, Hildago said.

In this context, they decided to accept Chequeado's invitation because "this initiative goes a step further and aims to introduce this practice at the level of journalism professors, to bring it closer and for it to be more common in academia," Hidalgo said. "There is a gap in [Latin American] universities and this project attempts to bridge it, starting from two principles that are essential to understand. First, fact-checking encourages students' critical thinking at a time when access to information can generate noise and confusion. The second point is that fact-checking methodologies favor argumentation skills, which are the essence of journalism: one must inform, but also explain and teach."

The Colombia Check project is part of the Latam Chequea collaborative network that works on fact-checking projects in the region. They decided to also join this network of trainers due to the lack of opportunities, in Colombia and the rest of Latin America, in higher education around fact-checking.

"There are almost no master's degrees, postgraduate or certified programs except for the MOOC [from the Knight Center], the Maldita.es master's degree and a couple of universities in Spain. So there are no university professors with formal knowledge to teach it," Jeanfreddy Gutiérrez, director of Colombia Check, told LJR.

Colombia Check and the other organizations in the network have plans to train teachers during the months of July and August, so they can teach it in classrooms starting next academic year, which begins in September. "There are few fact-checkers in the region and we are too busy to meet the training needs of universities. For this reason, teachers will be recruited to take on the commitment to implement what they have learned in their classrooms once the training is completed," Gutiérrez said.

Since its founding in 2017, Verificado has trained more than 600 journalists in topics ranging from fact-checking to journalism with a gender perspective, corruption and data journalism. They have developed a teaching methodology, since one of Verificado's missions, in addition to combating misinformation, is media education.

"There is a huge gap in everything that has to do with new communication techniques at the university level. It is very complex to modify curricula in educational institutions. These are very long and bureaucratic processes," Daniela Mendoza, general director of Verificado, said. (Photo: Courtesy)

"We are committed to media and information literacy, and to train our journalism colleagues. In fact, training and education are the main sources of income for our news outlet," Daniela Mendoza, general director of Verificado, told LJR.

Given this background, they decided to join the network of fact-checking trainers. During June they will launch a specific call for submissions and will hold an informative session to inform professors about the methodology they will follow. Because Mexico is a large and diverse country, Verificado aims to have different parts of the country represented and they are considering the participation of 10 to 15 professors from both public and private universities.

"There is a huge gap in everything that has to do with new communication techniques at the university level. It is very complex to modify curricula in educational institutions. These are very long and bureaucratic processes. It also happens that many professors may have been out of the labor force for many years and are not familiar with the new formats. At the end of the day, this makes it difficult to see the need to update educational programs," Mendoza said.

According to Mendoza, this network of trainers seeks to incorporate these contents "so that students are not left without this information. So they do not have to wait to graduate or take a course elsewhere because the curriculum in their degree does not offer these opportunities.